Word count: ~7700 | Est. read time: 41 mins

Main text:

Preface of The Encyclopaedia of Magical Creatures:

“Any creature ever imagined can be discovered in the tapestry of reality, as long as enough of the worlds have been explored.”

Loong

(Disambiguation: Western Dragon, Nāga, Quetzalcōhuātl, Yurlungur1)

Loongs, or Chinese Dragons, are formidable creatures widely featured in the legends of humanoid intelligent beings.

Feng Xiaoxing2, a historian, believes that they once truly inhabited Earth, the birthplace of human civilisation. However, no validation from the fields of biology or archaeology has emerged to back his hypothesis.

In year 456 of the star calendar, the first fossil remains of loong-like creatures were unearthed on Planet Tageve by biologist Loong Draco. Thereafter, the Milky Way Galaxy enters the “Loong Seeking Era” and Loong Seekers have emerged as a third profession to traverse the entire galaxy, after the book collector and the history observer.

With the repeal of the Anomalous Creature Isolation Act, loong-like beings engineered through gene manipulation by Imaginative Life Corporation are now widely distributed across planets inhabited by humanoid intelligent beings. Consequently, the profession of Loong Seekers has gradually disappeared.

This entry was authored by Tang Ming, the most renowned loong seeker in all worlds.

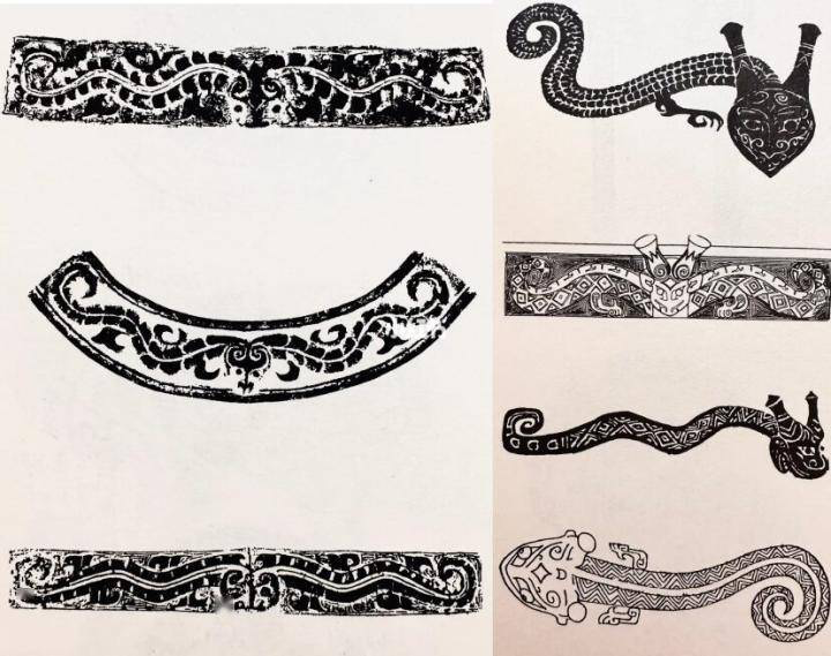

Evolution of the Image

In ancient Earth legends, the appearance of the loong was never fully settled, with “serpent-like, scaled bodies” as the only constant, other physical features continuously changing over time.

The earliest known loong-shaped artifact is a 1.92-meter-long sculpture of a pig-headed stone loong. Discovered in 1982 in the old calendar, it can be dated back to the Xinglongwa Culture3, which flourished in human civilisation from 6000 to 5500 BC in the old calendar. Featuring a pig’s skull and an S-shaped flat figure without limbs, it is believed to represent a crocodilian dragon.

Another loong sculpture of the same design was unearthed in 1987 at the Chahai Giant Dragon Ruins, which can be dated back to the Chahai Culture in around 5500 BC in the old calendar. It is also a 19.7-meter-long crocodilian dragon without limbs4.

In the later Yangshao Culture dating back to around 5000 BC in the old calendar, the loong-shaped mound sculpture underwent some changes as it started featuring four limbs. For example, in a tomb discovered in Xishuipo, Puyang, Henan Province, China, a loong-shaped creature composed of clam shells totalling approximately 1.87 meters in length was depicted with four limbs.

In this “Loong and Tiger” tomb, a loong made of shells was placed on the left side of the deceased, and a tiger on the right, which is considered the earliest “Four Symbols” formation

In the subsequent Hongshan Culture, jade artifacts predominantly featured C-shaped loongs and jaded-pig loongs, making it difficult to discern if they had limbs.

In the later Erlitou Culture and other cultures of the Xia and Shang dynasties, loong’s image generally depicted a coexistence of both four-limbed and limbless dragons, that started having tiger-like heads and antlers on their foreheads. Over time, their bodies evolved from early crocodilian and beast-like forms to more serpentine shapes.

From the Zhou Dynasty onwards in ancient China, the form of loongs became increasingly diverse, with standardised features such as horns on the head, whiskers near the mouth and a tail.

By the Qin Dynasty, loong’s image was basically established as four-limbed and clawed creatures. Nevertheless, during the pre-Qin era, Ying Loong, a winged dragon documented in The Classic of Mountains and Seas, was revered as the Ancestral Dragon of Creation5.

It is only until the Han Dynasty when loong’s image became largely stabilised, with its snake-like form becoming predominant while earlier crocodilian and beast-like depictions were phased out.

It is noteworthy that during the Han Dynasty, with the introduction of Buddhism, the figure of “Nāga” from ancient Hinduism was assimilated into Chinese culture and merged with the Chinese dragon, the product was regarded as the “Dragon King”, leading to a certain degree of transformation in the image of loong in ancient China.

In Shuowen Jiezi, a dictionary of Chinese characters compiled during the Eastern Han Dynasty, loong is described as “the master of all scaled creatures. It can be elusive or radiant, small or gigantic, short or long; it ascends to the heavens at the spring equinox and dives into the depths at the autumn equinox.”

From the Tang Dynasty onwards, the image of the wingless Pan Loong began to appear more frequently than that of the winged Ying Loong.

During the Song Dynasty, loong’s nose gradually took on the shape of a “ruyi” (a Chinese scepter symbolizing good fortune) to further enhance its auspicious symbolism. Additionally, the loong’s mane, dorsal fin, and flowing tail were also fixed. In the Southern Song Dynasty’s Explication of Erya: Loong Volume6, the concept of “Nine Resemblances of the Loong”, that has been widely used ever since, was clearly established as follows: “Its horns resemble those of a deer, its head a camel, its eyes a hare, its neck a snake, its belly a giant clam, its scales a fish, its claws an eagle, its palms a tiger, and its ears a cow. Alongside its mouth are whiskers, a pearl lies beneath its chin, and under its throat is a reverse scale. It can soar through clouds and travel across water, safeguarding a region7”. Of course, alternative interpretations also exist, such as “the loong’s horns resemble those of a deer, its head an ox, its eyes a shrimp, its mouth a donkey, its belly a snake, its scales a fish, its feet a phoenix, its whiskers a human, and its ears an elephant.8”

By the Yuan Dynasty, the image of the loong was basically finalised and has since been preserved till this day.

In Ming Dynasty’s Bencao Gangmu: Wings Volume, it is stated that “Loong is the supreme among scaled creatures. According to Wang Fu9, its appearance shows nine similarities: the head resembles that of a camel, the horns a deer, the eyes a rabbit, the ears an ox, the neck a snake, the abdomen a giant clam, the scales a carp, the claws an eagle, and the paws a tiger. Its back is covered with eighty-one scales, corresponding to the number representing yang. Its roars are as bright as the striking of a bronze plate. It has whiskers by its mouth, a pearl beneath its chin, and a reverse scale under its throat. On its head grows a sarcoma-like bulge called Chimu, without which it cannot ascend to the heavens. Its breath can form clouds, and it is capable of spouting both water and fire.”

Although the image of dragons gradually became stable since the Qin and Han dynasties, the concept of the Loong itself underwent increased differentiation, leading to a broader range of classifications beyond Ying Loong.

In Guangya: Explanation of Chi from the Three Kingdoms period, loongs were further subdivided into four categories: “those with scales are classified as Jiao Loong, those with wings Ying Loong, those with horns Qiu Loong, and those without horns Chi Loong.” Another view prevailing during the same period held that those with a single horn were Loongs or Dragons, those without horns were Chi, and those without feet were Zhu.

Shuyiji (“Records of the Strange and Unusual”)10 from the Northern and Southern Dynasties introduced an evolutionary chain among different types of dragons: “a Shuihui can transform into a Jiao after five hundred years; a Jiao can turn into a Dragon or Loong after a thousand years; a Loong can evolve into a Horned Loong after five hundred years, and after another thousand years, it changes into a Ying Loong.” In this context, “Shuihu” refers to all aquatic creatures, while “Loong” denotes Chi Loong and “horned Loong” means Qiu Loong.

During the Yuan Dynasty, the five-clawed loong emerged, which, alongside the Eight-loong and Nine-loong designs, was later prohibited by the government for any private use. Instead, these symbols can be only applied on royal attire11.

During the Ming Dynasty, The Zhangguo Astrology12 proposed that “a true dragon possesses auxiliary wings”, while The Spring and Autumn Annals of the States13 from the same period articulated that “the dragon devoid of wings is Pan Loong14. A dragon with wings is the Flying Dragon, symbolizing the emperor. As I hold the position of the Chief Minister, ranking just below the emperor, my symbol is thus Pan Loong.” The “true dragon” and “Flying Dragon” here both refer to Ying Loong. By then, the image of loong began to be associated with emperors and was gradually established as a symbol of the royal family15.

By the Qing Dynasty, the five-clawed golden loong16 became a symbol of the emperor, and the convention of subordinate states using only four-clawed or three-clawed loongs began to take shape17.

It is evident that Chinese dragon or Loong has evolved from its early forms—crocodilian, serpentine, and bestial—into the contemporary serpentine dragon image. In contrast, Western dragons were predominantly serpentine in their early depictions. It was not until the 13th century that the beastly dragon forms became prevalent. Subsequently, with the rapid transformation of multiple information dissemination media, the Western dragon’s image was essentially established as a winged, lizard-like beast.

Capabilities and Behaviours

The capabilities of loongs, much like their physical image, have evolved over time.

The specific capabilities of loongs prior to the Xia and Shang dynasties still remain a mystery. However, during the Shang dynasty, loongs predominantly lived in waters, although some inhabited mountainous regions (such as Chi-Loong18) and a few resided in the sky (such as Ying Loong). Their abilities were also related to water, including inducing rainfall and controlling floods. Consequently, in rituals related to praying for rain and expelling floods, loongs were always prominently featured, though they were not the main characters in these ceremonies. Additionally, loongs from this period were also believed to possess the ability to fly.

Interestingly, pre-Qin literature reveals that loongs could be domesticated by humans. For instance, the surname “Huanloong” (Dragon Raiser) was bestowed by Emperor Shun to a group of people who made a living by raising loongs19. During the reign of Emperor Kongjia, a man named Liu Lei learned the art of loong-rearing from the Huanloong clan. He raised loongs for Kongjia and even served loong meat to the emperor, for which he was granted the surname “Yuloong” (Dragon Tamer)20. This suggests that during the Shang and Zhou periods, loongs were not particularly powerful, with some even becoming domesticated livestock of humans.

By the pre-Qin period, loongs were described to increasingly reside in the heavens, primarily serving as mounts for deities and could transport mortals to the celestial realm.

By the Han dynasty, loongs have developed the ability to alter their size and length freely, to turn invisible, to soar up to the sky and dive into waters (as noted in Shuowen Jiezi).

Following the introduction of Buddhism, the abilities of the Chinese dragons began to merge with those of the Hindu “Nāga” , leading to significant enhancements in loongs’ water-controlling power. Their status was also elevated to the “Dragon King”, who ruled over all waters including oceans, lakes and rivers. Consequentially, loongs became the key character in relevant rituals such as rain-making ceremonies.

The supernatural abilities of loongs, such as water spouting, fire breathing and summoning of lightning, were attributed to loongs in the Ming Dynasty, largely thanks to the flourishing novel industry of that era.

Thus, it can be safely concluded that the earliest loongs primarily dwelt in water, and would sometimes be found in mountains and the sky. They possessed the capability to dive underwater and fly across the skies, and would have some powers in controlling water.

The later abilities of loongs, derived partly from Nāga and the imaginations of novelists, are beyond the discussion.

Loongs in Real Worlds

Tageve Loong

The Tageve Loong was discovered on Planet Tageve, a mid-high gravity planet with a surface gravity that is three times that of Earth.

This planet has a dense atmosphere rich in carbon dioxide, argon21 and oxygen, with traces of methane, ammonia and sulfur dioxide, and a density of up to 120 kilograms per cubic meter22.

It is abundant in water, with oceans covering 55% of its surface. The landmasses are divided into two major continents and three large islands. Due to frequent geological activities, the planet experiences regular volcanic eruptions, resulting in highly dynamic atmospheric conditions.

The vegetation system in the planet is highly developed, with various types of tree-like plants exceeding 100 meters in height, forming vast forest ecosystems. These plants, much like Earth’s vegetation, are capable of absorbing carbon dioxide, methane and ammonia while producing oxygen. The terrestrial and aquatic organisms on Tageve are abundant, though airborne creatures are quite rare. The only known living species in its sky is a six-limbed creature resembling a pterosaur, that has a pair of wings and four hind limbs. Its wingspan can grow up to 10.2 meters, and its hind limbs are powerful with claws connected to venom sacs through blood vessels.

Tageve Loong is an extinct species from the Planet Tageve, with fossil evidence suggesting its existence approximately one million years ago. It measured approximately 55 meters in total length, with a serpent-like elongated body that was estimated to be about 5 meters in diameter, and a pair of wings that was around 80 meters in length and 10 meters in width. The specifics of its tissue structure and feathers remain unclear.

The skeleton of the Tageve Loong is notably distinct from that of common Earth organisms. Its trunk is composed of 207 vertebrae connected by ball-and-socket joints23, with the main part of each H-shaped vertebra connecting to the flat bony plate, within which are the neural canals, extending upward and downward at the ends of the plate. The downward extension contracts into a rib-like structure that forms the abdominal cavity, while the upward extension bends into a shorter bony plate instead of a rib-like structure. This skeletal arrangement may evoke comparisons to the Stegosaurus of ancient Earth, albeit with bone plates positioned laterally rather than dorsally.

Analysis of fossils reveals the presence of a substantial air sac located between the bone plates on both sides of the dorsal region. Notably, air sacs within each vertebral cavity are not interconnected but controlled uniformly by a singular neural bundle.

In addition to having huge air sacs, archaeologists have identified that the muscles of the Tageve Loong were exceptionally well-developed, suggesting it possessed considerable explosive powers.

For a long time, the function of these air sacs remained unclear. Furthermore, investigations into the Tageve Loong’s wings indicated that they were insufficient to support its weight in flight, suggesting that the wings were more suited for gliding rather than flying.

It was not until planetary meteorologists simulated the evolution history of Tageve that the function of the air sacs in the Tageve Loong and its capacity for flight became clear. Computer simulations revealed that one million years ago, the atmosphere of Tageve showed a pronounced stratification. The lower atmospheric layer, rich in argon, sulfur dioxide, carbon dioxide and methane, was dense and turbid, thus being referred to as the “Turbid Layer”. Conversely, the upper layer, mainly composed of carbon dioxide, ammonia and oxygen, was less dense, and hence labelled as the “Clear Layer”. The Turbid Layer was estimated to have a thickness of between 1,500 and 2,500 meters while the Clear Layer extended from 6,500 to 8,500 meters. This unique atmospheric structure resulted from prolonged tectonic movements at the boundary between two major continents, where a towering volcano’s crater even extended beyond the atmosphere, directly channelling much of the atmospheric disturbances caused by geological activities into space, thus maintaining stable atmospheric conditions for an extended period. However, this stability ended with an asteroid impact one million years ago, which redirected tectonic movements and created numerous new volcanoes especially undersea ones. These volcanic activities disrupted the entire atmospheric structure, causing the disappearance of its stratification.

Under this stratified atmospheric structure, space palaeontologists hypothesise that the Tageve Loong could utilise its well-developed musculature to propel itself and then glide into the upper atmosphere by flapping its wings to catch the air currents. Once they enter the clear layer, the loong’s air sacs would fill with the significantly less dense air, allowing it to fly freely after returning to the turbid layer. Moreover, fossil evidence suggests there existed colossal tree-like plants towering over 500 meters, which could serve as the starting points for loongs to ascent into the clear layer.

Naturally, as the two-layer atmospheric structure was disrupted, the Tageve Loong lost its ability to fly and could only glide. Due to the lower average density of the re-mixed atmosphere compared to that of the original Turbid Layer, Tageve Loongs’ gliding capability in the new era was significantly reduced, which explains why they almost became extinct within less than 1,000 years after the change.

More intriguingly, fossil evidence indicates that the Tageve Loong had a unique set of robust and hypertrophied muscles at the neck region, connecting the trachea and the oral cavity. These muscles exhibited severe keratinisation on their inner surfaces and inside the cuticle were flammable elements such as white phosphorus. Given the high concentrations of methane and ammonia in the turbid layer, space palaeontologists hypothesise that the Tageve Loong could breathe fire by rubbing these muscle groups to ignite the surrounding air. In the visually constrained turbid layer, this ability is used more for attracting other creatures than for attacking, much alike the anglerfish24 in Earth’s deep sea.

The Tageve Loong is the first real loong ever discovered by humanity. It possessed both the abilities of flight and fire-breathing, although it remains unclear whether it could dive underwater, and it is not believed to have the power to control the rain. Moreover, its existence was heavily dependent on the unique atmospheric conditions of Planet Tageve one million years ago, making it a one-of-a-kind entity in the known universe. Therefore, such a creature could not exist on Earth. However, its existence raises the intriguing possibility that loong-like beings described in ancient human legends might indeed inhabit some other corners of the cosmos.

The Tageve Loong is also known as the “First Loong of All Worlds”.

Karot Loong

Karot Loongs live on Planet Kaio.

Planet Kaio is known for its extensive, intersecting, net-like geological structures on the surface. These structures are based on towering and continuous mountain ranges that extend almost entirely in a single direction. There are two sets of such mountain ranges, oriented in a different direction. The set with a smaller angle relative to the equator is the “Latitude Range”, while the other set is the “Longitude Range”. The angle between the intersecting ridges of the two sets ranges from 70 to 75 degrees. Each set consists of exactly 20 ranges, dividing the entire surface of the planet into 800 rhombic grid regions.

The origin of this structure remains unclear to planetologists. Mainstream theory suggests that this peculiar topography may have resulted from the simultaneous impact of two similarly sized colossal asteroid collisions on Planet Kaio in its early history. Nevertheless, the formation of such towering mountain ranges remains an astonishing phenomenon.

With a surface gravity that is approximately one-quarter that of Earth, Planet Kaio is classified as a typical low-gravity planet.

However, its atmosphere is denser than that of Earth, with a density of about 1.05 times greater than Earth’s atmosphere. The atmospheric composition is mainly oxygen, which constitutes up to 45% of the atmosphere, followed by nitrogen, carbon dioxide and a small but significant amount of krypton25.

The significant height of these mountains results in distinctive climates within each grid on Planet Kaio while still maintaining overall consistency, creating a highly unique climatic system. As a result, while the high-altitude regions of Planet Kaio can undergo planetary-scale hurricanes, each grid may present contrasting meteorological phenomena, as one grid may be experiencing torrential downpours while another enjoys gentle breezes and sunshine.

Karot Loongs reside within the grid near the equator on Planet Kaio and are capable of utilising their flight ability to move into several adjacent grids for predation.

This native grid (a term used by astrobiologists to refer to a nesting grid where a non-global species predominantly resides) of Karot Loongs is primarily a desert with limited water sources, containing water only in two large oases. Additionally, the surface temperature of this grid is exceedingly high, which planetary geologists attribute to the thin crust in the region and a large magma chamber located just below the ground.

Due to the high oxygen levels in Planet Kaio’s atmosphere and the fact that native organisms breathe oxygen, these organisms generally exhibit a higher metabolic rate compared to those on Earth, resulting in larger body sizes26.

The Karot Loong has a highly flexible body, capable of altering its cross-sectional shape under its own muscular control. Its skeleton is hollow and fragile, often fracturing under the pressure from its own muscles. However, its organs have evidently evolved to adapt to this condition, with the outer membranes being remarkably strong, preventing them from being penetrated by fractured bones.

The Karot Loong has a long, serpentine body, measuring approximately 20 meters in length, with a cross-sectional width and height both under 0.5 meters. Its body is covered in highly reflective scales that can rapidly vibrate under muscular control, producing a distinctive buzzing sound. These scales form the unique vocal organ of the Karot Loong. Its head resembles that of a lion, with a dense mane surrounding it, and its protruding mouth is like that of a horse. Its two eyes are positioned on each side of the face, leaving a central blind spot in its vision. Below the eyes is the lower jaw with two long bundles of whiskers.

The Karot Loong also possesses numerous air sacs within its body, although unlike the Tageve Loong, these air sacs share the elongated abdominal cavity with other organs rather than being housed in a separate dorsal chamber. A total of 18 air sacs are symmetrically distributed along its torso. These sacs can both expel air directly outside through air vents and channel air into the lung lobes connected to the sacs via internal airways. Its small and numerous lung lobes are distributed around the air sacs and encased in thick muscle, though they do not form independent lungs.

Therefore, the air sacs of the Karot Loong serve not only as respiratory organs but also serve as crucial flight organs.

In fact, as encased by strong muscles, the air sacs can expel high-velocity air streams when the muscles contract rapidly, with its speed reaching up to 300 m/s27.

Of course, such speed alone is not sufficient to enable the Karot Loong to take flight. Its ability to fly relies on the fact that it can reshape its body into an airplane wing-like trapezoidal structure, generating additional lift through rapid undulating movements28. More importantly, the Karot Loong is highly skilled at capturing updraft to glide effortlessly along its path.

The two clusters of whiskers behind the Karot Loong’s mouth, each with 8 strands of whiskers measuring 5 to 8 meters, are covered in fine fuzz sensitive to air currents. These serve as both auditory organs and airflow sensors, allowing the dragon to detect updrafts near the grid’s mountains and glide from its nesting grid to adjacent ones.

Actually, the Karot Loong is not a formidable competitor within its own nesting grid, where it is preyed upon by various large, swift but flightless predators. However, it becomes a top predator in the surrounding grids due to the lack of natural enemies and aerial competitors.

While Planet Kaio is home to various aerial hunters, the Karot Loong’s flexible body allows it to entangle other avian creatures and subdue them with bites and venom injection. For smaller avians, a single strike from its tail can be lethal.

The Karot Loong has two unique methods of attack. On the one hand, it secretes an anaesthetic liquid in its air sacs and expels it at high velocity to create a cloud of anaesthetic mist. On the other hand, it inhales the venom secreted by the venom sacs in its mouth, mixes it with stomach acid and then expels it by compressing the muscular system surrounding the stomach. This highly toxic fluid is lethal to other creatures and poses a significant threat even to the Karot Loong itself. These two attack methods have made it the “sky dominator” of Planet Kaio.

However, Karot Loongs are unable to incubate their eggs internally due to their cold-blooded nature. Instead, they must bury their eggs in sand piles of their home grid to incubate them by geothermal heat. This dependence on external heat prevents them from venturing too far from their grid to further rule the entire Planet Kaio.

The reliance on geothermal heat also poses a critical vulnerability for the species. Within its grid resides a worm-like soft-bodied organism called the Geosaurus, which can burrow through sand rapidly and feeds on Karot Loong eggs. The Geosaurus is a natural predator of the Karot Loong, and the latter has almost no effective defence against it except for laying more eggs to increase their survival rate.

As a result, the Karot Loong has been a minor species. Furthermore, as their nesting grid is located near the pole, an area among the last to be explored by humans, Karot Loongs remained undetected for a long time.

Unfortunately, the first human expedition in encountering the Karot Loong led to an avoidable large-scale conflict (the vibrating scales of the Karot Loong produce infrasonic waves29 that would by chance cause internal organ damage in humans), resulting in mass slaughter of this species. This tragic incident severely worsened Karot Loongs’ precarious survival. Currently, fewer than 1,000 Karot Loongs lives on this planet and their numbers are declining at a rate of 10 to 20 individuals per year. The species has been classified as endangered by the Intergalactic Scientific Regulatory Commission.

Colopic Loong

Colopic Loongs inhabit the Planet Mekna, a unique planet with an exceptionally strong magnetic field.

This planet has a diameter amounting to roughly one-third that of Earth and a surface gravity that is only one-tenth as strong. However, its core is unusually active, with a rapidly spinning iron core and a stable rotational axis. As a result, Mekna’s magnetic field is incredibly strong and consistent—approximately 2,000 times the average magnetic field strength of Earth30. Mekna is therefore a particularly unique low-gravity and high-magnetic-field planet.

All lifeforms on Mekna are silicon-based rather than carbon-based, with flat and hard skeletons made of silicon-nickel alloys, but they can be quite brittle at the same time (though relatively speaking, they are far from fragile to humans).

Their muscle tissue consists of a silicon-based elastic memory material, capable of swiftly transitioning between various structural configurations in response to changes in voltage and temperature. Their brains are composed of a complex three-dimensional matrix of silicon wafers and granules, with light-emitting components facilitating inter-layer communication—an advanced and highly efficient neural system. Anatomical studies, however, reveal the absence of a centralised clock mechanism within the brain, resulting in asynchronous activity across different brain regions. This can lead to neurological irregularities such as seizures, memory disarray, cognitive dysfunction and even dissociative identity phenomena, accounting for the erratic behaviour commonly observed in the planet’s fauna.

The Colopic Loong is among the largest indigenous species on Mekna and the only one capable of flight. It possesses two forelimbs adapted for hunting, and dissection has revealed that its hind limbs have become vestigial, leaving only two tail fins that function primarily in directional control. A fully-grown Colopic Loong measures around five meters in length, a considerable size on this planet. Its forelimbs, though short at just 0.5 meters, end in three razor-sharp claws each, capable of effortlessly slicing through nearly all native Mekna creatures.

Colopic Loongs typically measure 1 meter in width and 0.6 meters in height, with a cross-sectional profile resembling an elongated oval. Their surface is covered by silicon-based scales, functioning similarly to reactive armour when under attack. Beneath these scales is the torso covered by muscles akin to memory ceramics, though which the skeleton is connected without any joint structures like ball-and-socket joints. Consequently, the Colopic Loong has a highly flexible body capable of extensive twisting and unexpected shearing movements. However, its muscle fibres are highly constrained directionally, allowing it to only be able to twist horizontally.

The Colopic Loong’s head features two eye zones with compound eyes capable of perceiving a vast range of electromagnetic waves, from radio waves to X-rays, granting it an extraordinarily “broad vision” even by Mekna’s standards. It has a crocodile-like flattened snout and dendritic whiskers used for electromagnetic sensing (the whiskers do not sway since Mekna has no air). With its overall dark purple colour, the appearance of the Colopic Loong is rather intimidating, like a spectral dragon from hell.

The Colopic Loong’s ability to fly stems from its unique physiological adaptation: the asymmetrical distribution of its blood vessels, with arteries concentrated on the left side and veins on the right. This arrangement allows the iron-rich blood to generate a stable electric current across its body, creating a powerful magnetic field that interacts strongly with the planet’s geomagnetic field to enable it to levitate.

This explains why this dragon is only found in the planet’s southern polar regions.

Interestingly, no “Anti-Colopic Loong” with similar principles has been identified in the northern polar regions.

The Colopic Loong can not only generate a stable magnetic field for flight but can also control its internal blood flow to produce localized electromagnetic bursts, which serve as a deadly attack method against other Mekna creatures and even human electronic devices. Conversely, if a Colopic Loong is flipped onto its back, it will not only lose its ability to fly but also be unable to turn itself back over, leaving it doomed to a slow death.

For this reason, Colopic Loongs primarily live at high skies away from other ground-dwelling creatures, only descending to lower altitudes when hunting for prey.

Chamuya Loong

The Chamuya Loong resides on the Planet Kame, a planet initially named after its indigenous giant terrestrial tortoise-like creatures known for their delectable taste.

Planet Kame possesses vast water resources, with oceans covering almost 80% of its surface, leading to an atmosphere saturated with water vapour. Coupled with significant levels of nitrogen monoxide, carbon dioxide and ozone, the planet experiences an intense greenhouse effect. As a result, its surface temperatures remains consistently above 50°C, rendering it highly inhospitable to human life. But its water resources can be used to support several nearby colonial space stations.

Additionally, Kame’s geomagnetic field is notably strong—though not as powerful as that of Mekna, it still reaches about 500 times the strength of Earth’s magnetic field. Moreover, unlike the stable geomagnetic field of Mekna, its field is prone to experience relatively frequent reversals similar to Earth’s, with a cycle ranging from 1,000 to 10,000 years31.

Much like the Colopic Loong, the Chamuya Loong also relies on magnetic fields for flight. However, in contrast to Colopic Loong’s reliance on the circulatory flow of iron-rich blood, the Chamuya Loong ascends by swallowing magnetic minerals.

In fact, the Chamuya Loong can crush rocks with its teeth, spit out non-magnetic elements and absorb magnetic ones into a special stomach. This stomach doesn’t participate in digestion but only stores the magnetic minerals. It can transport these minerals through highly responsive muscular conduits to other parts of the body freely, allowing the dragon to levitate with remarkable control. This ability is theoretically superior to that of the Colopic Loong, whose poor directional control limits it to specific regions.

Nevertheless, the Chamuya Loong is the smallest among all loong-like creatures, with a fully grown individual reaching a mere meter in length and about 0.3 meters in cross-sectional width, which represents the largest ratio of body width to length in all loong-like creatures. Coupled with its flat head and snout, this loong resembles a crocodilian dragon rather than a serpentine one.

Whereas most dragons are predators, the Chamuya Loong is an herbivorous prey species. Its magnetically-assisted flight is a specialised adaptation that evolved during its long history of evasion. Intriguingly, a local humanoid ape-like species has been found to have mastered the art of domesticating Chamuya Loongs, treating them as aerial mounts. In this regard, the Chamuya Loong echoes the loongs of ancient Earth during the Shang and Zhou periods.

Linkri Loong and Jiao Loong

The Linkri Loong and the Jiao Loong were once considered to be two different loongs. However, it was later discovered that they are actually different forms of the same species.

Linkri Loongs and Jiao Loongs both live on Planet Fustero but in different environments. Jiao Loongs dwell in the oceans, particularly in the deep sea, while Linkri Loongs are airborne creatures. This ecological separation has led to the long-standing misconception that they are separate species.

Planet Fustero is a giant gas planet rather than a solid one like Earth. However, unlike many gas giants, it owns distinct surface layers32, with an upper atmosphere composed of helium, hydrogen, alkane and olefin gases and a lower “ocean” primarily made of liquid hydrogen.

Remarkably, within Fustero’s ocean exist floating islands that are mainly composed of solid hydrogen, including metallic and glassy forms. They can remain stable for extended periods before gradually dissolving into the liquid hydrogen ocean33.

In addition, Planet Fustero has an extremely active core, resulting in intense electromagnetic activity throughout the planet, along with ocean currents and crucial material flows driven by the shifting electromagnetic fields.

An extraordinary ecosystem has therefore evolved around these floating islands. Within it, most marine creatures have metallic hydrogen as their skeletons, with alkenes and alkynes long molecular chains forming their muscles, endowing them with impressive swimming abilities. Among these incredible life forms, Jiao Loong is the largest.

Nevertheless, even the largest Jiao Loong can only reach the length of 1.5 meters.

The head of Jiao Loong closely resembles that of Jiao Loong from Chinese mythology except that it is made of solid hydrogen. It appears crystal-clear under light like a gemstone artwork, which led to Jiao Loongs being relentlessly hunted by poachers for a long time.

Moreover, Jiao Loong possesses a powerful electromagnetic sensing ability, allowing it to manipulate the electromagnetic fields around its body to influence ocean currents. This grants it true control over water, enabling it to feast on small fish and shrimp by directing surrounding water flows toward its mouth.

Jiao Loong is the true ruler in the ocean of Fustero as it faces no rivals. However, due to its immense size, it swims quite slowly and has to reside for extended periods in the biologically rich deep-sea regions near Fustero’s solid layer, which is filled with solid hydrogen, methane ice and other solid substances. Of course, it will occasionally venture into shallower waters, either for play or a change in taste.

Above the ocean of Fustero lies an 80-kilometer-thick atmosphere mainly composed of hydrogen, helium and hydrocarbon gases. This atmosphere, characterised by extreme density and high flow velocities, is governed by six major cyclones. Even such an extreme atmosphere harbours a few organisms, which typically possess flattened bodies with delicate glassy hydrogen skeletons covered in thin molecular chains. These aerial creatures are experts at utilising air currents for movement and are predominantly carnivorous, often preying on each other. They primarily inhabit regions with relatively stable air currents and frequently settle on small solid hydrogen islands on the ocean surface. Some also venture to the uppermost levels of the atmosphere, harnessing sunlight as an energy source.

Among these aerial organisms, the Linkri Loong stands out as one of the most exceptional, with its range extending from the ocean’s horizon all the way to the edge of space. Nevertheless, not even the mighty Linkri Loong dares to approach the cyclones.

Humans have long been puzzled by the existence of these creatures as the scarcity of potential food sources in the vast atmospheric expanse makes it difficult to understand how they sustain themselves and reproduce. Observations of their reproductive processes have long been elusive, with them seemingly appearing out of nowhere. However, given the immense scale of Planet Fustero — approximately 1.5 times the size of Jupiter — such a result is not surprising.

Similarly, the marine life in the ocean of Fustero presents numerous mysteries. For instance, not a single ancient marine organism, including the Jiao Loong, has ever been observed. It seems that Jiao Loong never ages, with only three life stages including egg, juvenile, and adult. Death seems to occur instantaneously, as if it suddenly tears the creature apart.

It was only later discovered that aerial beings like the Linkri Loong are not independent species but rather a special form of marine life in their final stage. This revelation unveiled the intricate ecological system of the Planet Fustero.

Take the Jiao-Linkri Loong as an example. Throughout its long life, the Jiao Loong continuously consumes various organisms, repeatedly heating, pressurising and condensing them within its body. Ultimately, the metallic hydrogen in these organisms is converted into glassy hydrogen, giving birth to new Linkri Loongs. Once the Linkri Loongs are fully formed, the Jiao Loong’s mission is complete. At this point, it ascends to the ocean’s surface and performs a dramatic self-destruction to release the Linkri Loongs into the atmosphere. The remaining body then becomes nourishment for other marine and aerial creatures.

Thus, Linkri Loongs represent the second phase of the Jiao-Linkri Loong. They continuously fly in the atmosphere, seeking suitable companions. Towards the end of their life, two or as many as five or six Linkri Loongs will cluster together and sink into the ocean floor. During this process, they dissolve each other’s bodies and manipulate electromagnetic fields to accumulate materials to form a new egg based on their skeletons. From this egg, a new Jiao Loong emerges.

This is a magical life cycle. The Jiao Loong phase can last up to 100 years, while the Linkri Loong phase spans over 50 years, and the process of re-congealing into an egg takes 10 years, making the complete life cycle of the Jiao Loong-Linkri Loong about 160 years.

Due to Jiao Loong’s unique commercial value, its population has dropped to a dangerously low level within less than a century after being discovered by Loong Seekers. Although the number of Linkri Loongs has not immediately plummeted, the overall trend remains concerning. Some planetary biologists believe that the ecological environment of Planet Fustero may have suffered irreversible damage as the remains of Jiao Loong are a crucial food source for surface-dwelling marine life in the ocean and Linkri Loongs play a vital role like pollinators in distributing the seeds of other similar two-phase life forms across the planet. Hence, the Intergalactic Scientific Regulatory Commission is working actively to classify the Jiao-Linkri Loong as an endangered species. However, this initiative confronts strong opposition from human commercial alliances.

Leraa Loong

Technically, Leraa Loong is not a biological entity but rather a phenomenon.

It exists on the Planet Devas and is named after a tycoon who first purchased the planet (the practice ceased to exist as trading of planets was later prohibited). Planet Devas bears a remarkable resemblance to Earth in many aspects, with its atmospheric composition being nearly identical to that of Earth, with surface gravity only 0.03% less and rotation and orbital periods closely aligned with those of Earth. The only distinctions is its diameter, which is 1.3 times that of Earth, and its more stable climate.

It seems to be more suitable for human habitation than Earth in every respect.

However, its native creatures exhibit extraordinary abilities, surpassing humans in mobility, attack power and defense strength. Although there are no intelligent beings akin to humans (despite the discovery of ancient civilization remains in a valley), these life forms remain dangerous for ordinary Earth humans.

Following humanity’s initial arrival on the planet, ongoing conflicts between them and native species emerged, resulting in substantial casualties among humans. They had to employ military-grade weapons to eradicate indigenous creatures in order to establish a base.

The phenomenon known as Leraa Loong appeared many years after the establishment of human colonies. Initially, not enough attention had been paid to it, and it was only dismissed as an illusion or figment of imagination.

Specifically, Leraa Loong represents a collective phenomenon consisting of a large aggregation of insects. And most amazingly, this swarm encompasses not merely a single species but five to ten distinct types of insects.

They seemed to receive specific commands, as they would suddenly leap and attack individuals or small groups of humans upon their arrival at designated locations.

During the attack, all these insects fly together at very close distances but never collide with each other, forming a long twisting loong-like formation that extends over 20 meters in length and 1 meter in width. Due to their close proximity, the swarm appears as a single blue-grey loong rather than a group of insects. The exact colour of the “loong” may vary depending on the composition of insects, with most of them appearing slate-grey, while some may be bright red.

The capabilities of swarms vary depending on their insect composition. For instance, the swarm can rapidly consume all objects within it, including titanium alloy exoskeletal armour, when a critical mass of Aragon insects are included. When a sufficient number of Shoggoth insects are present, the swarm shows the ability to discharge small-scale lightning due to the electric organ cells34 within these insects. A swarm containing a significant number of crimson Magnus insects can produce formidable infrasonic and ultrasonic attacks. Most intriguingly, when both Magnus and Ragnus insects reach a critical threshold, the Ragnus insects—previously considered harmless—can release a highly pungent and spicy liquid with a temperature reaching up to 90 degrees Celsius35. Additionally, Hypnos insects, characterised by their silver-white colouration, can create a low-temperature environment. While they cannot “exhale fire” like Ragnus insects, any area traversed by a Leraa Loong composed of Hypnos insects will experience a temperature drop to almost freezing point.

Thus, in terms of abilities, the Leraa Loong phenomenon is the closest to the mythical loongs, but unfortunately, it is not a real dragon.

Till now, the origin of the Leraa Loong phenomenon remains undetermined. Some believe that these insects are manipulated by some external force, be it certain humans aiming to seize Planet Devas or the native intelligent beings who prefer to remain hidden for various reasons. Alternatively, proponents of the Gaia hypothesis posit that the swarms are actually controlled by the planetary consciousness of Planet Devas. The most recent sighting of a Leraa Loong phenomenon occurred in the year 574 in the star calendar, when five swarms of Leraa Loongs with different abilities attacked human settlements together, ultimately leading to the permanent abandonment of Planet Devas by humans.

Pāpīyas Loong

The existence of the Pāpīyas Loong still remains a subject of controversy.

It does not inhabit a particular planet but rather exists within black hole jets. Some even claim to have seen it within the accretion disk of a black hole.

Despite the general consensus that life is unlikely to live in the vacuum of space or black hole jets, there is photographic and video evidence of the Pāpīyas Loong within black hole jets, making its existence seemingly indisputable.

In the first definitive observation of a Pāpīyas Loong, it was approximately one light-year in length, completed a head turn over a period of ten years and had an epic encounter with the cosmologists’ observational instruments.

Subsequent observations of similar phenomena in other black hole jets have suggested that these sightings are not merely coincidental formations of jet material resembling a loong’s head.

It is hypothesised that the Pāpīyas Loong may be a projection from an alternate spacetime membrane, made observable due to the high energy of the black hole jets. Alternatively, it is also proposed that the Pāpīyas Loong may be a genuine dragon living within the black hole jets, feeding on high-energy particles.

While they attempted to end this debate, the scientific community was at a loss, as entering the black hole jets to observe the Pāpīyas Loong is undeniably a deadly task.

- Western concept of dragons originated from the ancient Greek word “Draco”. The Nāga, a serpent deity in the legends of India and other South Asian countries, merged with the Chinese concept of the “Loong” after being introduced into China through Buddhism, though it is more accurately classified as a “jiaoloong” in Chinese mythology. Quetzalcōhuātl, the Feathered Serpent, is a deity in Mesoamerican legend, capable of controlling rain and bringing maize to the region. Yurlungur is a deity in Australian Aboriginal belief, also governing agriculture and weather. ↩︎

- The name “Feng Xiaoxing” is a variation of “Ma Xiaoxing”, the author of Loong: An Unidentified Creature. Ma Xiaoxing was formerly an editor at the Shanghai Lexicographical Publishing House and Shanghai Bund magazine. However, in the real world, he cannot be considered a historian. ↩︎

- The Xinglongwa culture, dating back approximately 8,000 to 7,500 years, is a Neolithic civilisation located in Inner Mongolia and Northeastern China regions, predating the Cishan, Yangshao, and Hongshan cultures. ↩︎

- The stone loong sculpture discovered in 1987 at the Chahai site in Fuxin, Liaoning, is known as the “First Dragon of China”. Both the Chahai culture and the Xinglongwa culture belong to the early Neolithic period, with a significant overlap in their timeframes, though they exhibit notable differences in cultural characteristics. The Chahai culture is the precursor of the Hongshan culture and is honoured as the “Homeland of the Jade Loong and the Cradle of Civilization”. ↩︎

- The image of the Ying Loong is essentially consistent with contemporary loong representations, but it features an additional pair of multicoloured wings and yellow scales, it was thus also known as the “Yellow Loong”. In the beliefs of that time, the Ying Loong was responsible for creation and salvation, and by the Song Dynasty, it was attributed with the power to destroy the world. Additionally, the Ying Loong is said to have given birth to the Qilin and the Phoenix, earning it the title of “Ancestral Dragon”. According to legend, the Ying Loong assisted Fuxi in creating the Bagua, helped Nuwa mend the heavens, aided the Yellow Emperor in defeating Chiyou, Kuafu, and Yan Emperor, and supported Da Yu in controlling the floods. ↩︎

- Both Erya Yi and Erya are ancient dictionaries, with the former considered a supplement to the latter. Interestingly, while Erya contains detailed descriptions of the phoenix, it provides no depiction of the loong’s image. This omission was addressed in Erya Yi, where the loong’s appearance was added. ↩︎

- A similar perspective can be found in Experiences in Painting (T’u-hua Chien-wên Chih) by the art connoisseur Kuo Jo-Hsu, who lived during the same period. ↩︎

- This view was also held by Dong Yu, a painter from the same era. ↩︎

- A politician, litterateur and thinker of the Eastern Han dynasty. ↩︎

- A collection of stories similar to The Records of Strange Tales featuring stories about ghosts and the supernatural occurrences written by mathematician and astronomer Zu Chongzhi of the Southern Dynasties. ↩︎

- The History of the Yuan Dynasty records: “The emperor initially prohibited commoners from wearing items such as qilin, phoenix, white rabbit, ganoderma, double-horned five-clawed loongs, eight loongs, nine loongs, the character of longevity, and ochre-yellow objects”. Prior to the Yuan dynasty, the loong was only mentioned alongside other mythical creatures in a series of motif patterns in The Rites of Zhou, without particularly emphasising the connection between the loong and the imperial family. ↩︎

- A work on traditional Chinese astrology written during the Ming dynasty, often referred to as the “founding text of star studies”. ↩︎

- Also known as The Chronicles of the Eastern Zhou Kingdoms, it was compiled by Yu Shaoyu during the Jiajing and Longqing periods of the Ming dynasty, adapted later by Feng Menglong during the late Ming dynasty and further edited and commented on by Cai Yuanfang during the Qianlong period of the Qing dynasty. Along with The Tale of King Wu’s Conquest of Zhou, it became one of the prototypes for the supernatural novel The Legend of Deification. ↩︎

- It was from the novels of the Ming dynasty that Loong gradually became a symbol of the royal family, henceforth evolving into the tradition where the five-clawed loong is associated with the emperor, while vassal states were only permitted to use the four-clawed or three-clawed loongs. This is an example of customs that were inspired by imagination. The wingless Pan Loong, assumingly having reduced might and power, was also hence seen as a “lesser form of dragon”. ↩︎

- The imperial items used in the Yuan dynasty mainly featured the wingless Pan Loong. Although the Ming dynasty inherited the rule of the Yuan, the loong motifs and images used in the palace reverted to the Ying Loong since the Han dynasty. ↩︎

- The five-clawed loong refers to a loong with four limbs, each having five claws. The five-clawed golden loong should be the Ying Loong as it is considered a true dragon. Additionally, the wingless Pan Loong is increasingly viewed as a “true dragon that has yet to ascend to the heavens”. ↩︎

- The term “Descendants of the Loong” originated in 1978 in the famous song with the same name, written and composed by musician Hou Dejian. It gained widespread popularity after being covered by Li Jianfu in 1980, becoming a sensation in campuses. The song was performed twice later on CCTV’s Spring Festival Gala in 1985 and 1988, after which the term “Descendants of the Loong” spread across China. But in the Ming and Qing dynasties, the loong was primarily a symbol of the imperial family, commoners were not permitted to refer to themselves as “Descendants of the Loong”. Before the Yuan and Ming dynasties, the association between loongs and emperors was even less pronounced, and Chinese people did not consider themselves as “Descendants of the Loong”. At that time, the loong was merely regarded as one of many mythical creatures. ↩︎

- Note that Chi-Loong (炽龙) is to be differentiated from Chi Loong (螭龙) introduced above. ↩︎

- Some believe that loongs were worshipped by the Huanloong clan instead of being raised; however, there is no evidence to support this assertion. ↩︎

- Recorded in the Guoyu: After the decline of the Taotang clan, Liu Lei later learned dragon taming from the Huanloong clan and raised loongs for Kong Jia, the Emperor. He was then granted with the surname Yuloong (Dragon Tamer) and the fiefdom that previously belonged to the Shiwei clan. ↩︎

- A colourless, odourless and non-toxic inert gas with an atomic weight of 40. It is commonly used in industrial applications for welding. ↩︎

- Approximately 100 times the density of Earth’s atmosphere. ↩︎

- This vertebrae structure resembles that of a real snake. ↩︎

- The anglerfish is a bioluminescent fish that inhabits the deep sea. It has a long, fleshy protrusion with a glowing sac at the tip, which is rich in bioluminescent bacteria that attracts other fish in the deep sea for predation. ↩︎

- Also an inert gas that is colourless, odourless, and tasteless, commonly used as filling gas in gas lasers, plasma chambers, particle detectors, light bulbs and neon tubes. ↩︎

- In comparison, during the era when dinosaurs thrived, the oxygen content in the atmosphere was approximately 35%, higher than that in modern-day air, thereby allowing for the existence of large organisms with higher metabolic rates like dinosaurs. ↩︎

- The highest speed achieved by humans through their own physical effort is 506 km/h or 140.5 m/s, in the Guinness World Record for a badminton smash. ↩︎

- The prototype for this setting is the golden tree snake on Earth, which can deform its body in this manner and glide for more than 10 meters through propulsion. ↩︎

- This is a real phenomenon associated with sound wave hazards. Both infrasound and ultrasound can potentially damage human organs or the nervous system. ↩︎

- The level of the Earth’s magnetic field ranges from 0.22 to 0.67 gauss. In comparison, a refrigerator magnet has a strength of about 100 gauss. ↩︎

- The Earth’s magnetic field reversal cycle is about 450,000 years; however, the intervals between each reversal can vary significantly. For instance, the most recent reversal occurred around 780,000 years ago. ↩︎

- The atmospheres of many gas planets transition continuously into their liquid bodies without distinct boundaries. ↩︎

- These states of matter are possible within gas planets as some theories suggest that Jupiter may also contain metallic and glassy forms of hydrogen. ↩︎

- A cell found in the muscle tissue of the electric eel that is used for generating electricity and producing an electrochemical potential difference. ↩︎

- Some insects in the real world do possess the ability to regulate their temperature; for example, certain moths can generate heat in their thorax while flying. However, 90 degrees is indeed a bit far-fetched for real insects. ↩︎

Translation Editor: Xuan